Dr. Steve Gallon lll, imported con-man & former Plainfield superintendent was banned from working in New Jersey schools in May 2010.

Gallon & his (2) assistants, Angela Kemp & Lalelei Kelly were arrested for; false documents, theft by deception, conspiracy to commit theft by deception, and false swearing.

Although this TRIO faced these serious charges, they were all welcomed with open arms into the cesspool of corruption, that is MDCPS.

Gallon & his (2) assistants, Angela Kemp & Lalelei Kelly were arrested for; false documents, theft by deception, conspiracy to commit theft by deception, and false swearing.

Although this TRIO faced these serious charges, they were all welcomed with open arms into the cesspool of corruption, that is MDCPS.

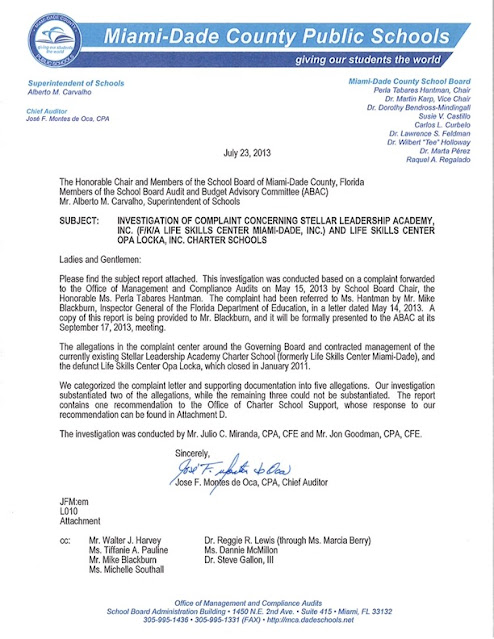

Soon after his arrival at MDCPS, Gallon, a never-quitter when it comes to scandals & corruption was investigated for his ties to Stella Leadership Academy Charter Schools AKA Likfe Skills Center Miami-Dade. July 23, 2013, the investigation was completed from a complaint into (5) allegations involving Gallon. (2) out of the (3) claims were "substantiated".

Apparently, Dr. Gallon III is a habitual traffic offender while using his privilege to illegally park in handicap spaces & speed in school zones.

Dr. Steven Gallon III: Family Pride

In a strange tale of events, Dr. Gallon chose to have a sexual affair & impregnate a Parent instead of a student, breaking the MDCPS employee status quo.

A paternity suit was filed on 11/08/2021 at the Broward County Clerk of Courts.

Steven Gallon VS Teniseshia Nicole Jones

Let's not leave out Dr. Gallon's son, Steve Gallon lV & all of his criminal accomplishments.

Before being exposed to the general public by various individuals in the 1990s and 2000s, the Boulé was on par with white organizations like Skull and Bones – people knew they existed but couldn’t really prove it.

Meaning “Council of Chiefs” or “Adviser to Kings” in Greek, the Boulé was for much of its existence an elite, invitation-only secret society for Black men of high regard. Members are chosen based on their professional accomplishments and community standing.

In a 2011 interview, political researcher and speaker Steve Cokely called the Boulé an “illegal criminal enterprise” full of “Black complicity in this centralization of worldwide power the new world order.”

By Kyra Gurney

A Miami-Dade School Board member lost his license to teach in Florida on Thursday after legal controversies in New Jersey followed him to Florida.At a hearing in Naples, Florida’s Education Practices Commission revoked School Board member Steve Gallon’s educator’s certificate, which enables him to work as a school principal and English teacher, and permanently barred him from reapplying for certification.The revoking of his certificate will not strip Gallon’s position on the School Board, where he has been outspoken about numerous issues, including the district’s oversight of struggling schools in poor communities and its spending on school construction. But it could prevent Gallon, who currently works as an education consultant, from ever returning to the classroom as a teacher or administrator.Gallon’s attorney, Levi Williams, called the decision “harsh and unjust.”The commission chose the toughest possible penalty instead of opting for lighter sanctions, such as a fine or a written reprimand.“The system failed us in delivering a just decision,” Williams said. “Dr. Gallon is a life-long educator and servant of our community and we’ll review all our options.”The commission’s decision was based on the revocation of Gallon’s school administrator certificate in New Jersey, where he served as the superintendent of Plainfield Public Schools from 2008 to 2010.Gallon was arrested in 2010 over allegations that he used a false address to enroll his godsons in school. The charges were later dropped and Gallon does not have a criminal record in New Jersey. The New Jersey Department of Education revoked Gallon’s school administrator certificate in 2012.That means Gallon is in violation of a Florida statute that gives the Education Practices Commission the right to discipline educators who have had their certificates revoked or suspended in another state, the commission found.Gallon and his attorney argued that the allegations in New Jersey were politically motivated and that Gallon’s years of service to the Miami-Dade school district should be weighted against his troubles in another state.Gallon started his career as a teacher in Liberty City and rose through the ranks, serving as an assistant principal and later as the principal of Miami Northwestern Senior High, a position he held for seven years.Gallon also worked as a school district administrator overseeing alternative education programs for at-risk students before moving to New Jersey.Once in New Jersey, Gallon told the commission, he ran into political opposition. “I did not stand for the status quo that consistently failed those children,” Gallon said, explaining why he feels he was targeted.The commission noted Gallon’s work in Florida, but decided to uphold New Jersey’s sanctions. The state didn’t make it clear if Gallon’s action would have violated Florida’s standards for educators.“I appreciate your commitment to education and your lifelong service, but that does not erase what we are here to discuss today and I very much believe that we need to uphold what New Jersey is doing at this time,” said Christie Gold, the commission’s presiding officer. Commission members told Gallon that if he is able to obtain a new certificate in New Jersey, the commission would be willing to reinstate his certification in Florida.The initial complaint against Gallon was filed in June 2016, after Gallon had declared his candidacy for the District 1 School Board seat he currently holds. Williams said the complaint was filed by a disgruntled former business partner.“I certainly think when he decided to run some of his opposition certainly took advantage of the situation in New Jersey to use the complaint process in Florida to try to taint him,” Williams told the Miami Herald two days before the hearing.This is not the first time Gallon’s New Jersey arrest has haunted him in Florida. The issue came up repeatedly during last year’s School Board campaign, with Wilbert “Tee” Holloway, a former board member Gallon defeated, and other critics bringing up the scandal at candidate forums.In a statement issued after the hearing, Gallon said the decision “in no way impacts my educational or professional service.”“My attorney will review next steps while I remain focused on my service to the students, staff and community,” he said.School Board members are not required to have a teaching certificate or any education experience. While the commission’s sanction does not affect Gallon’s standing as a School Board member, it could impact his ability to get public support for future board proposals.School Board Chair Larry Feldman declined to comment on the revocation, other than to say that Gallon “is in good standing” with the board. A spokesperson for the school district said that “it would be both inappropriate and unfair to comment on a duly elected board member serving on our School Board.”UPDATE: This article has been updated to state that Steve Gallon does not have a criminal record in New Jersey. Gallon provided the Miami Herald with a copy of a letter from New Jersey’s Office of the Attorney General stating that Gallon does not have a criminal record.

By William Gjebre, FloridaBulldog.org

A former Miami-Dade County school principal/district administrator banned from working in New Jersey public schools following an investigation during his tenure as superintendent of a 7,000-student district is seeking a seat on the Miami-Dade School Board.

Steven Gallon III says his New Jersey troubles, including an arrest for theft, were “driven by politics.” Likewise he disputes allegations surrounding his firm’s management of a trio of South Florida charter schools and his authority to hire and set salaries. “That had nothing to do with me,” Gallon said in an interview.

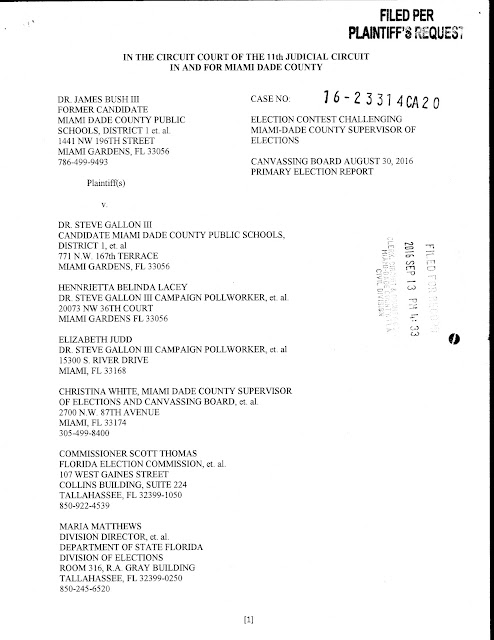

With the school board election set for Aug. 30, Gallon has a sizeable funding lead in his attempt to unseat District 1 incumbent Wilbert “Tee” Holloway.

According to the latest campaign reports filed with the Miami-Dade elections office, Gallon has raised $65,120; Holloway, $17,900; and another candidate, James Bush III, $4,685.

Gallon, who worked his way up from teacher to principal at Miami Northwestern Senior High from 1998-2005 to district administrator in Miami-Dade public schools, said he’s running because District 1 needs a change.

“…The schools in District 1 continue to languish in the areas of student achievement, educator quality and support, and other areas that will ensure the learning and lifelong success of our students,” he said in a prepared statement to FloridaBulldog.org.

Aware of the funding gap, Holloway said the election is “not about money.” He said he believes he has done a good job for the parents and students in his district and hopes voters will support his re-election.

Holloway declined to comment about controversy surrounding Gallon, including his tenure in New Jersey. It is for the voters to decide, he said.

New Jersey controversy

In 2008, Gallon was hired as superintendent of the Plainfield, N.J., public schools at a salary of $198,000. Not long afterward, controversy enveloped the new superintendent.

First, the New Jersey Department of Education found that two of three Miami colleagues that Gallon hired did not have the required certifications for their $100,000-plus positions, according to a New Jersey media report. After the finding, the two, Lalelei Kelly and Lesly Borge, were fired by the school board, the report stated.

Despite the news report, Gallon said in his statement, “Only one of the four from Florida had an issue and was erroneously placed in the wrong position by Human Resources when hired and prior to my arrival as superintendent.”

Furthermore, he stated, “… with respect to the certifications of staff, I requested a state inquiry and the state concluded that I did no wrong and there were issues with nearly 30 other employee[s] that were employed by the district prior to my arrival and under the responsibility of the Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources.”

Following the certification issue, Gallon, Kelly and Angela Kemp, his third assistant from Miami, were charged with stealing more than $10,000 worth of educational services, according to a press release from the Middlesex County Prosecutor’s Office, which filed the charges in May 2010.

The prosecutor’s press release said Gallon was charged with “conspiring to commit theft by deception, theft by deception as an accomplice, and false swearing.” Kelly and Kemp were charged with “uttering false documents, theft by deception, conspiracy to commit theft by deception and false swearing,” according to the press release.

The allegations involved Gallon, then a South Plainfield resident, declaring under oath that the two assistants and their children lived with him while the children attended a local school, the prosecutor’s office said. The assistants actually lived elsewhere, according to the prosecutor’s office.

The lies allowed the children to attend school in South Plainfield, costing that district $10,500 during a five-month period, after which the children were moved to a school where they actually lived.

After their arrests, Gallon and his two assistants took a deal that allowed them to enter a pretrial intervention program with the condition they never work for New Jersey public schools in exchange for their charges being dismissed, according to New Jersey media reports. Gallon’s two assistants repaid the money, according to a news report in New Jersey.

‘What benefit or gain was there?’

In a statement, Gallon blames his troubles on politics.

“Due to politics I was accused of allowing my two godsons – ages 6 and 7 to reside with me and legally attend school in my area for a brief period of time. Where I’m from we take care of our children and provide shelter and support where needed. I was making $225,000 a year. The parents were making six figures. What benefit or gain was there? There was no ‘theft’ and the school district they were enrolled [in] can attest to that.”

Gallon said he decided to leave New Jersey because of its “slow wheels of justice” and to “attend to my mother whose health was failing.”

He also claimed that “no one was banned from working in New Jersey,” though public records and media reports indicate otherwise.

Following a review by the New Jersey Department of Education’s Board of Examiners Gallon’s administrator certificates were revoked in June 2012. A department document states the board upheld the provision Gallon signed in the “consent agreement” to “never seek nor accept employment in any New Jersey public school or public system.”

In August 2014, a New Jersey state appellate court turned down a request by Gallon’s two assistants, Kelly and Kemp, to revoke the ban prohibiting them from working in state public schools.

After the controversy in New Jersey, Gallon and his company, Tri-Star Leadership, were hired in June 2011 to provide educational services at three charter schools in Broward, Palm Beach and Miami-Dade counties, according to a June 2014 story in the South Florida Sun Sentinel.

The paper said that by the end of summer 2012 Gallon had obtained positions for the two associates arrested and banned from working in the New Jersey public schools, made payroll decisions without approval of the three charter school boards and entered into a business with one of the volunteer board members of a charter school.

Despite the controversy surrounding the three schools, state ethics officials found that no laws had been broken.

Two of the three charter schools, Success Academy in Fort Lauderdale and Excel Leadership Academy in West Palm Beach, shut down in the summer of 2013. Miami’s Stellar Leadership Academy remains active.

Gallon said the three schools had management problems before his company was hired. “I had no authority to hire, fire, pay, or even write checks at either school,” Gallon said in his statement.

Nothing “improper or illegal” occurred, he said.

By Amy Shipley and Karen YiNew Jersey authorities banned educator Steve Gallon III from working in their public schools. Five months later, three South Florida charter schools welcomed him.

The struggling schools gave Gallon’s company $500,000 in taxpayer dollars over two years, allowing him to give jobs and double payments to his cronies, a Sun Sentinel investigation found.

Records obtained by the newspaper reveal questionable decisions at the schools as their finances unraveled, providing a rare look into the perils of Florida’s loosely regulated charter-school industry.

State law gives oversight of these schools to individual volunteer governing boards, rather than the district’s school board. But such boards sometimes fail to monitor public money and control the private companies they hire, the Sun Sentinel found.The governing boards for three charter schools in Broward, Palm Beach and Miami-Dade counties hired Gallon and his company, Tri-Star Leadership, in June 2011.

The boards were undeterred by Gallon’s troubles as a school superintendent in New Jersey, where back-to-back investigations prompted the governor and police to get involved. Gallon had been accused of hiring unqualified friends and then lying about their residences so their children could attend schools outside their district.In the next 18 months, documents show, the South Florida charter school boards stood by as Gallon:

• Hired two associates who, along with Gallon, had been arrested and banned from working in New Jersey schools. One became principal of the Palm Beach County school at a salary of $80,000 a year; the other was paid $60,000 a year for consulting work.

• Made payroll decisions without prior authorization from the charter schools’ governing boards, drawing rebukes from the schools’ financial consultants.

• Hired a $40,000-a-year consultant who listed her residence as a Georgia home owned by Gallon.

• Launched a business venture with one of the volunteer board members responsible for overseeing Gallon’s work for the charter schools. The venture was later deemed a conflict of interest by Miami-Dade school district investigators.

At least three consultants contracted by the governing boards warned their bosses of inappropriate actions under Gallon, records show. Yet Gallon stayed on as those who complained quit — or were fired.

“Once we found out there were problems in these schools, we warned the boards of directors of these schools,” said Katrina Lunsford, a Lakeland-based consultant hired by the schools’ governing boards to provide financial and budget management services.

She also said: “How many warnings do you have to give? How much documentation do you have to give?” she said. “We went from one school to the next school to the next school.”

Lunsford resigned from one school and then was fired from two others in late 2012.

Success Leadership Academy in Fort Lauderdale and Excel Leadership Academy in West Palm Beach closed in the summer of 2013. Stellar Leadership Academy in Miami faced financial struggles but rebounded and continues to employ Gallon’s company.The Sun Sentinel examined hundreds of documents including payroll, correspondence, and other records attached to complaints filed by Lunsford and an associate with the Florida Attorney General’s Office and other state and local entities.State ethics officials who investigated the complaints last year found no laws had been broken, but the documents reviewed by the newspaper detailed lax oversight and a host of failings at the three charters.They also underscore a key weakness in Florida’s law, the newspaper found: State statutes governing the conduct of public officials do not apply to the private operators that often gain power at charter schools, even though public money is at stake.decline to issues beyond the board’s or Gallon’s control.Both traditional public schools and charter schools receive public dollars based on their enrollment, and don’t charge tuition. Administrators at traditional public schools are accountable for every penny spent. But the private companies hired by many charter school governing boards don’t have to open their books.

The Sun Sentinel left messages with several board members who were at the three schools during Gallon’s tenure, but only one responded. Reggie R. Lewis, president of the board at the Broward school and board vice president at the Miami-Dade charter, attributed the Broward school’s

Gallon, 45, declined to answer questions from the Sun Sentinel, but issued two statements through a Tri-Star spokesperson. The spokesperson wrote that the company supported the “mission of serving and supporting the educational needs of at-risk and underserved students” and ensured “that only qualified, experienced, and credentialed consultants provide support to the Board and school.”

The spokesperson also stated: “Despite accusations and subsequent independent inquiries and investigations, there has been and remains no determination of any wrongdoing or improprieties on the part of any present or former board members or educational professionals that were subjects of your inquiry.”The three high schools for at-risk students were reeling when their boards hired Gallon. The schools opened in 2005 under a private management company that selected the original board members and handled all school operations, from real estate and payroll to busing and curriculum. That company, White Hat Management of Ohio, operated a number of charter schools throughout Florida and began pulling out of the state in 2011.While many of the company’s Florida schools folded, the boards of these three charters decided to carry on. They turned to Gallon to help get them on track.TROUBLE IN NEW JERSEYGallon began his career as a middle-school teacher in Miami, ascended to principal of Miami’s Northwestern Senior High, and then served as a district administrator in the Miami-Dade school district.

Plainfield, N.J., schools hired him as superintendent in 2008, paying him $198,000 a year to oversee the central New Jersey district of about 7,000 students.

The back-to-back scandals quickly erupted.

Soon after his arrival, Gallon brought on three colleagues from Miami at six-figure salaries. Investigators from the New Jersey Department of Education concluded that two lacked proper state certification and one of those two lacked a required degree.

To address the issue, Gallon recommended hiring them under different titles that did not require certification.

Gov. Chris Christie then stepped in, calling for New Jersey’s education commissioner to take action, according to news reports. A day later, the School Board fired the pair, Lalelei Kelly and Lesly Borge.

Less than a month later, in May 2010, police arrested Gallon, Kelly and Angela Kemp, the third Miami hire. The state Attorney General said Gallon falsely claimed the women lived at his address in South Plainfield — a school district in which they neither lived nor worked.

The trio’s lies, prosecutors said, enabled both women’s children to attend South Plainfield schools illegally and cost taxpayers $10,500 over four months. The women later paid back the money, records show.

In January 2011, Gallon and the two women agreed to serve probation and never again work in New Jersey’s public schools. In exchange, the charges were dismissed.

The following year, the three reunited — in Florida’s charter-school system.FRIENDS IN FLORIDAGallon knew one of the board members at the three South Florida charters; they’d worked together years before in the Miami-Dade public school system. He also knew a consultant who worked for the schools, Tonya Deal, who recalled Gallon from their days as students at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee as a bright mind with great potential.Deal said she believed his version of the New Jersey scandal — the story was overblown by the media — and urged the schools to hire him.Gallon fully disclosed his past to the boards, said another board member, Lewis. She told the Sun Sentinel she believed Gallon’s arrest had nothing to do with his official duties in New Jersey, and noted that he had not been convicted of any crime.Gallon got the job. He was hired as a $135-per-hour consultant in June 2011. His mission: improving student performance at the three schools.The boards hired other contractors, including a payroll administrator, a security company, and Lunsford for financial management services. None of them, records show, rivaled Gallon in power.INCREASING AUTHORITYWithin a year, by April 2012, the boards gave Tri-Star more responsibility and roughly 15 percent of the state dollars allocated to the three schools. The company was assisting with day-to-day operations, and receiving as much as $60,000 a month from the three schools, records show.Deal had joined forces with Gallon by then, becoming his business partner at Tri-Star.Gallon also teamed with Lewis, one of his bosses on two of the boards, to work on a side business venture — a charter application for another school — for $9,000, records show.Investigators with the Miami-Dade school district later deemed that collaboration a conflict of interest, chiding Lewis but taking no action. Lewis acknowledged to state ethics investigators that she worked with Gallon on the project, but said she saw no problem with the collaboration because she did not pay Gallon. She said she paid only Tri-Star business partner Deal as an independent contractor.By the end of summer 2012, Gallon had secured jobs for three of his former colleagues— including the two women arrested and banned from working in New Jersey, Lalelei Kelly and Angela Kemp.Kelly signed a $60,000-a-year contract with Tri-Star to provide compliance, accountability and other services to the Broward and Miami-Dade schools.Gallon signed a contract on behalf of the Palm Beach County school making Kemp principal for $80,000 a year.And he brought on a third employee, Lenee Clarke, a former compensation administrator for the Plainfield Board of Education, for $40,000 annually to provide Tri-Star with various support services.Clarke listed a residence in Lithonia, Ga., registered to Gallon, according to payroll and property records.

Lewis told the Sun Sentinel the schools did not manage the hiring decisions of their vendors.PAYMENTS QUESTIONEDThe schools’ financial team began to caution the boards against overspending, flag certain payments, and raise concerns about Gallon’s seemingly unchecked authority.“I started warning board members,” said Lunsford, the financial manager.She also said: “He, from an overall standpoint, just started taking charge and taking over.”Records show the boards at times responded with indifference or hostility to issues raised by Lunsford and the accountant she hired to help her with the schools, Jim D. Lee.When Lunsford requested documentation for a $625 bank transaction on Sept. 25 from Dorothy Gay, the board president for the Palm Beach County school, Gay provided it — along with an indignant email:“Let the record reflect the following, which I will make perfectly clear this one time only and never again question me about any ‘funds’ or state to me, ‘show documentation’...”Other questioned payments in September elicited an outcry from consultants, two of whom promptly resigned. A pair of extra payments to Kelly that doubled her wages from $5,000 to $10,000 that month angered even school employees.“They’re asking me to cut staff, telling me they don’t have any funds, and I find out somebody is getting $10,000 in one month,” Cynthia Hazlewood, the Broward school’s interim principal, said in an interview with the Sun Sentinel.Kelly received the additional $5,000 from the Broward school even though its board approved only a $2,500 monthly boost. And that approval came weeks after Gallon already had authorized the pay hike by signing a contract on the school’s behalf, records show.Thomas Brown, the payroll administrator for all three schools, questioned the first extra payment, according to emails. Clarke also received payments in September that were later questioned by several consultants, district documents show. Gallon approved those payrolls, interviews and records show.“He paid people when the warnings were out,” Lunsford said. “He paid people when we said, ‘Hold up, there’s no money.’”Gallon, however, authorized no extra payments for himself, and Tri-Star received significantly less than its contract guaranteed from the Broward school that month, records show. About that time, Gallon also stated in emails that he did not wish to have payroll duties.Deal said she began to second-guess her push to bring Gallon to the schools. She resigned that month from Tri-Star. Brown, the payroll administrator, also quit. In letters to the schools’ boards, he wrote:“Due to our inability and unwillingness to continue to effectively collaborate with Dr. Steve Gallon we are discontinuing our payroll services ...”As fall neared, the financial team’s phone calls and emails gave way to written complaints lodged with board members.TABLED AT RED LOBSTERFaced with a mounting crisis, the governing board of the Palm Beach County school assembled for its October public meeting. By law, such meetings must be accessible to the public and allow an opportunity for input.Board members, however, did not gather at the school. They went to a Red Lobster.Lee, the Lakeland accountant, joined the meeting via conference call. Lee had warned that month in letters to the Palm Beach and Miami-Dade county schools that Gallon committed an “illegal act” when he made payroll decisions without board authorization. To all three schools, Lee made a series of recommendations to tighten financial controls, among them transferring payroll matters from Gallon’s company.But at the meeting in West Palm Beach, Lee was cut short, several people in attendance said. Gay said she had already discussed Lee’s letter with the board and “would be tabling the item until a later date,” according to meeting minutes.One of the board members who was present, Anthony G. Allen, resigned three days later. Neither he nor Gay responded to requests for comment.The boards for the Broward and Miami-Dade charters adopted most of Lee’s recommendations during their October meetings, including transferring payroll services from Tri-Star.The Broward board also rescinded the questioned stipends. That school’s attorney warned Tri-Star in a letter that its contract would be terminated if the alleged double payments and payment errors were not corrected or explained.But no extra payments were returned, financial team members said.The Miami-Dade school district later reviewed allegations that Gallon authorized payments and signed a contract without board approval but concluded the charges were not substantiated — citing only board minutes from the Miami-Dade school’s October 2012 meeting.Tri-Star remained under contract with all three schools, records show.THE END OF THE LINEBy the end of 2012, the boards for the charters declared states of fiscal urgency. Though the Miami-Dade school would recover in the coming months, the end was near for the Broward and Palm Beach county schools.Attendance at both schools fell dramatically from the prior year, in part because of moves to new facilities, dropping from 202 to 92 at the Palm school and from 241 to 88 at the Broward school. Because the schools receive public money based on their student population, the drop in enrollment resulted in a plunge in school income.The Broward school took a hit when its lease expired and a new charter took over its building, absorbing some of its students. The school moved from Oakland Park to Fort Lauderdale. The Palm Beach County school blamed the opening of another charter near its original location for its decline, according to state records. It, too, relocated.Gallon took no pay from the Broward school and reduced payments from the Palm Beach County charter in the final months of 2012. But both schools made occasional payments to him in early 2013 — even as debt accrued and teachers and staff quit.By spring, records show, a church that housed the Broward school demanded $15,000 in past-due rent; a security company claimed the Broward and Palm Beach county schools owed it nearly $20,000; and the Broward school district said it was owed more than $80,000 — an overpayment because of smaller-than-expected enrollment numbers.The two schools also were crumbling academically — the area Gallon had been hired to improve.The Broward school showed no evidence of a reading program, English language instruction for non-native speakers or services for students with disabilities, district officials reported. The school also provided false information about teachers, the officials said.The Palm Beach County school lacked a science teacher and did not offer core courses, district officials reported. A state administrative law judge found the school lacked reading lesson plans, study guides or even textbooks; “neglected” biology and math; and “failed in its most basic duties to educate its students.”Board member Lewis said Gallon and Kelly tried to help until the end, and were “the ONLY persons that continued to stay and work to try to save” the Broward school. Lewis said the pair worked without compensation for some time, and Gallon donated “nearly $8,000 in his own resources” to the school.“A person who has done wrong hides and runs, they don’t stay and stand,” Lewis said in an email to the Sun Sentinel.The financial team, Lunsford and Lee, lodged complaints in early 2013 with agencies across the state, which forwarded them to the Broward and Palm Beach county school districts. Neither district investigated.In June, the Broward school voluntarily shut its doors. In July, the Palm Beach County school was shut down by its district.

By Sue Epstein | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

PLAINFIELD -- The Plainfield superintendent of schools and two assistants were charged today with stealing more than $10,000 worth of educational services by providing false documents to send two Perth Amboy children to school in South Plainfield, Middlesex County Prosecutor Bruce Kaplan and state Attorney General Paula Dow announced.

Steven Gallon III, 41, a South Plainfield resident and superintendent of schools in Plainfield, was charged with conspiring to commit theft by deception, theft by deception as an accomplice and false swearing, Kaplan said.

His former assistants, Angela Kemp, 36, the assistant superintendent for educational services, and Lalelei Kelly, 34, who had worked as the district’s coordinator of assessment, data collection and school improvement, were charged with uttering false documents, theft by deception, conspiracy to commit theft by deception and false swearing, Kaplan said.

Gallon surrendered at the Plainfield school board offices this morning and Kelly surrendered to police in Perth Amboy. Kemp was arrested later at her home in Perth Amboy.

Superior Court Judge Frederick De Vesa today set bail at $25,000 each for Gallon and Kelly, who could post 10 percent of that amount for release from the Middlesex County jail. Kemp was expected to be taken to the jail as well.

The investigation by the state Division of Criminal Justice, the special prosecutions unit of the Middlesex County Prosecutor’s Office and the South Plainfield Police Department determined that on Aug. 14, 2009, Kemp and Kelly, who were residents of Franklin Township, enrolled their children in South Plainfield and provided false documents contending they lived in South Plainfield, authorities said. Kemp and Kelly provided a sworn statement by Gallon, who falsely indicated that the women and their children lived with him at his home at 921 Brennan Court in South Plainfield, authorities said.

In September, the women and their children moved to Perth Amboy, but the children attended school in South Plainfield between Sept. 2, 2009 and Jan. 20, 2010, when their mothers removed them from the district, authorities said. Authorities said Kemp obtained $5,600 in educational services for her child during the enrollment period, while Kelly obtained $4,900 in education services.

“The Plainfield Board of Education is gravely concerned about the allegations against Superintendent of Schools Steve Gallon III and Assistant Superintendent Angela Kemp,” said Agurs Linnard Cathcart Jr., president of the board, in a prepared statement.

Gallon came under fire last month in a report from the state Department of Education’s Office of Fiscal Accountability and Compliance that found neither Kelly who earned $113,550, nor a Lesly Borge, who earned $107,360 a year as coordinator of professional development and support services, had the qualifications required for their positions. The Plainfield board fired them last month. As for Kemp, a municipal court judge ordered her to step down from her position after being convicted of harassment for squeezing the neck of a principal during a staff meeting in September.

Gallon took over as superintendent in Plainfield on July 1, 2008 and makes $200,000 a year.

Denise Riley, a Plainfield resident, was the first one at tonight’s school board meeting to address the subject, well into the public comments section.

"I'm asking all of you board members, new and old, to look deep inside and make the corrections necessary and get rid of the cancer that is destroying our district."

The school board's counsel, Raymond Hamlin, said that any questions about revoking Gallon's contract were a personnel matter that could not be discussed publicly, but — "I have with me a court order that prohibits any action to be taken against the staff member that you refer to."

Jeremy Walsh, reporter for NJLNS, contributed to this story.

READ ABOUT THE OTHER ATROCITIES & THE CESSPOOL OF CORRUPTION THAT IS MDCPS

No comments:

Post a Comment